The Wall Street Journal recently hit 200,000 college-age women subscribers — a staggering number for a publication whose target demographic is usually men in their 50s and 60s.

While many point to the latest ad campaign that targets young women, that's only enough to get them in the door. There has to be something meaningful and interesting there for them to engage with — something that speaks to them and their needs — once they get there.

In February 2016, a few weeks after The Wall Street Journal launched on Snapchat Discover, the paper published a series on the demographic destiny of the world in 2050. One of the stories featured video interviews with young women from around the world about whether and when they thought they'd have children.

What could be more appealing to a young, curious mind than a demographic study on fertility rates? Literally anything, you say? You'd be right — but also surprised. It's all in how you spin it.

The Snapchat team decided to reexamine those videos, and recast the story under the auspices of "What Matters to Girls in 2016." In the edition, you meet five of the girls, each highlighting, in her own voice, one thing that mattered to her: education, career, marriage and children. You can watch the full edition here.

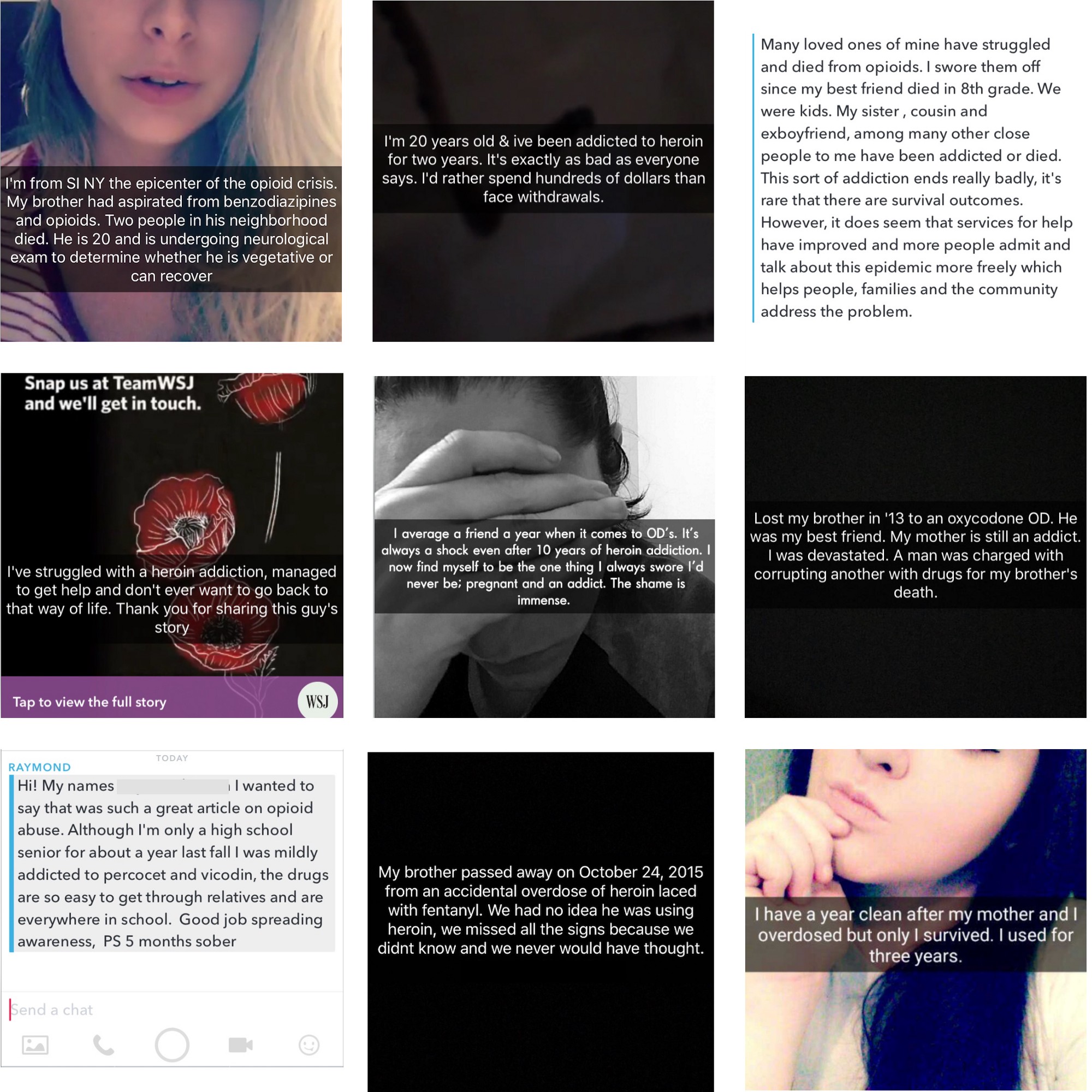

As the final snap in the edition, we tried our very first callout, asking "What matters most to you?" and giving four choices: education, career, marriage, and children.

In the 24 hours that the story was live, we received nearly 400 responses from young women, in the form of snapbacks, selfies, photos and chats. They were thrilled the journal was thinking about them, and covering their issues seriously.

We responded to every single individual who answered the question, whether through a selfie or a chat (many of the young women screenshotted the responses and sent messages like, "WHAT? Someone read this? MADE MY WEEK!"). Some we even went a step further.

Here, a 15-year-old girl reached out to say thank you, and let us know her dad was a big fan of the paper. I wrote back and encouraged her to borrow his copy and read the A-hed, a quirky story that runs daily on the front page of WSJ. The next morning, she sent me a shot of her at the breakfast table, sneakers just visible, with the Journal spread out in front of her.

I grew up in Salt Lake City, Utah, with a dyed-in-the-wool libertarian grandfather who loved the WSJ. I would sit at his kitchen table after school and read the A-hed while I ate a grilled cheese sandwich and chatted with my grandmother. From that spot, as a teenager doodling in the margins or using the stocks page as an impromptu napkin, I couldn't have felt farther away from the people who wrote those stories. But now, this young woman had the chance to reach out and make a connection inside the newsroom.

Is she going to be a subscriber today? No. But in 5 years, when she's deciding between an MBA, or an MFA or Law School, she'll remember that feeling she had, and who knows, she might just join the ranks of those 200,000 other young women who now "Read Ambitiously."